by Gerard H. Verhoeven

This is an updated and corrected version of my recollections "On Rail", which I started to prepare on 30 November 1974

from notes and studies I had made much earlier. I wanted to write this as a small tribute to my father, his colleagues, friends, acquaintances and the Dutch people who

went out and made the Netherlands East Indies the beautiful place it was before the Second World War. And let us not

forget the men, women and children of European descent who died or endured unspeakable treatment during that war.

I have tried wherever possible to use the present day Indonesian spelling of place names.

Dutch oe = Indonesian u, Tj = c, Dj = j, j = y: thus Tjepoe = Cepu, Soerabaja = Surabaya etc.

Dutch names were changed to Indonesian, i.e. fort becomes Benteng, Buitenzorg = Bogor, etc.

The Indonesian has difficulty pronouncing the v, making it a p, thus our surname Verhoeven was pronounced perhu-pen.

My family has told me that ever since I was a toddler I was mad about trains, and my daughters still tell me that. Why is it so fascinating to me? I liked the bustle of a big station in the heyday of rail transport, the rumble of trains going past, checking the origins and destinations of the cars passing by, the clickety-clack of long goods trains, the whistles and sounds in the night, no longer heard now, save for a diesel horn at a distance on a quiet early morning where I live now (Townsville, 1974).

I could in the stillness of the night visualise what the crew on a steam locomotive and the staff at a crossing station were doing, just by hearing the sounds emanating from the locomotive or the signal-box. I was always intrigued when I found a railway track, especially a narrow gauge one, crossing my road, wondering where it went, what it served, what ran on it?

Although my father and grandfather were both railway men, there was never any sign of interest in railway subjects from them. An interest in railways as a hobby was perceived to be juvenile and it was well into my adult years before I could openly express such an interest. I still remember furtively writing down engine numbers and details when I was working in a sugar mill in 1959. Railway photography was at best considered a waste of film and at worst, as spying. As late as 1976 I was pulled up by the railway police in Belgrade for taking photos from the train. Likewise, on the platform of Ski, an outer suburban station in Oslo, I was stopped by a young stationmaster who told me that it was an offence all over Europe to take pictures at railway stations, airports and harbours! I was taking a picture of a Christmas tree on the roof of his station!!

Thus, as a boy with an interest in railed traffic, I had to store it all in my memory till a later date when I could find out more about it.

When my Dad was on the station staff of the old Rotterdam Delftse Poort station (now "Centraal") I used to look in his coat-pocket when he came off night-duty for cubes of sugar he kept for me from his evening coffee. There is still a photo of my father in his Dutch Railways (NS) uniform with the continental-type departure staff in his hand standing next to a passenger carriage in the yard of the Rotterdam station. The station was badly damaged in the bombardment of Rotterdam (1940).

We used to live behind the station in the Harddravers st.22. My mother tells me that I used to put boxes and shoes all in a row on the floor to play trains and woe betide anyone who upset that row I was playing with. As far back as I can remember, I have had toy trains, and later, model trains in various gauges at home.

My grandfather began work in the railways in the last decade of the 19th century as a labourer in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. This place was rapidly expanding because of the burgeoning electrical industry being developed by Phillips, initially manufacturing light bulbs in a world that was rapidly changing from gaslight to electricity. Grandpa was soon in a signal box and as the railway yard grew and traffic increased all the time, he grew with the signal box in rank, retiring in the late twenties. Two of his three sons followed him on the railways, starting on stations near Eindhoven. Was this perhaps why I was attracted to anything running on two steel lines?

My father was a clerk, a "Commies" with the Dutch Railways (NS). In early 1928, he answered an advertisement for training as Sub-Inspector (or Assistant Superintendent of a railway district) with the Nederlandsch Indische Spoorweg Maatschappij (NIS), a private railway company with its head office in The Hague.

In those years, after the First World War and before the great world depression of 1929, there were often calls for European staff for the many colonial enterprises in what was then the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) and what is now Indonesia.

At the time my father was engaged by the NIS, the mainly European cadre of the company went to the Indies for 5-1/2 years and then had six months furlough with a return fare for the employee and his family to the Netherlands. Yearly there was a vacation of two weeks, which was generally spent at some nearby mountain resort with a cooler climate.

Society was very much stratified in those days and one travelled on the weekly mail steamers between Indonesia and the Netherlands according to the level of society to which one belonged. The four different classes were fairly strictly separated on board. We always travelled second class, which was the largest class both in terms of the number of passengers travelling and in the space allocated to it on the ship. These ships were like floating luxury hotels.

The NIS headquarters were in The Hague where the Board of Directors had a small administrative support staff.

The office of the NIS Council of Management in the Indies, presided over by a Chairman, was in Semarang, the capital of the province of Central Java. This office was in an ornate building, which is still the regional office of the PNKA (the Indonesian railway administration), at the beginning of the Bojong (now called Jalan Pemuda).

The NIS network was divided into sections under a District Superintendent, the EDB (a telegraphic abbreviation meaning highest ranking official). The Superintendent was generally a man with a strong railway background in traffic and commerce and he had a team under him such as a loco engineer and a way and works engineer. In later years these people were drawn from university educated personnel in law and engineering.

Cepu, East Java.

My first recollection is Tjepoe (Cepu, East Java). It was (is?) a divisional point. My father was a Sub-Inspector in the traffic and commerce branch then. Cepu is now on the mainline of the Indonesian Railways, Jakarta-Cirebon-Semarang-Surabaya. But in my time, part of this present mainline between Semarang and Soerabaja (Surabaya) belonged to the NIS and was classed as a tramline at first, although it ran on its own right-of-way. More about the history of this line later.

There were extensive teak forests around Cepu which were served by the tramways of "Boswezen" (State Forestry). The Forestry had its own rolling stock of the 3'-6"(1067 mm) gauge. I think originally the teak logs were floated down the Solo River for export. There was also an oil field nearby exploited by a Dutch company (BPM - Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij) which was later to become a subsidiary of Shell Oil.

Parties of railway enthusiasts visit Cepu nowadays (1995) to sample the operations of the trains of the forestry department.

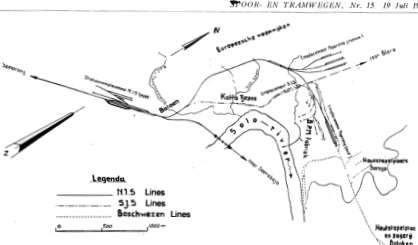

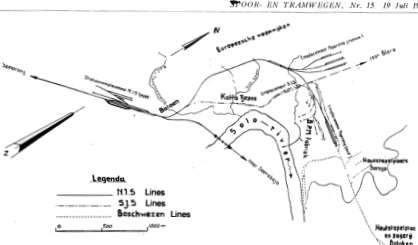

Some seventy years ago there was a lot of interesting railway working in and around Cepu. A colleague of my father wrote about this in the Dutch magazine, Spoor-en tramwegen (S&T) in 1938.

The SJS (Semarang Joana Stoomtram-maatschappij [Steam Tram Company]) reached Cepu in 1901 from Blora, while an NIS tramline of 3'-6" gauge was being built from Gundih to Surabaya. The SJS built a railway yard on the northern outskirts of Cepu and a short line into the town with a run-around siding. From its railway yard a siding curved east into the oil plant nearby, called Ngareng.

The BPM acquired some rolling stock of its own, bogey flat wagons to carry drilling material and a few 4-wheel open wagons. This rolling stock used the forestry department network to get to and from the drilling fields. The forestry department had its own rolling stock, consisting of locomotives, flat cars and some carriages to convey workmen.

The NIS opened its line from Gundih to Surabaya at Cepu in February 1903 and connected with the SJS loop siding in the town. The main NIS line continued towards Surabaya.

On 1 January 1914 the NIS opened a 3 km branch to Ngareng, which came off the connection between the SJS and NIS near a spot called Baloon and circled west of the town centre to cross the SJS line north of its goods yard to finish in an exchange siding with the tramway of the forestry department. In the exchange siding, a connection was made with the sidings of the SJS in the BPM oil plant.

From there on, the NIS did all the shunting at the BPM oil plant as well as picking up loads of teak and firewood from the exchange sidings, which were placed there by the locomotive of the forestry department. This change came about because the distance to Surabaya is shorter than to Semarang. Export loading in Surabaya was done at the quay-side, whereas in Semarang large ships had to stay in the roadstead.

North of the NIS/SJS crossing, the SJS made a siding that ran virtually parallel with the NIS exchange siding. This SJS siding connected with the forestry lines also and was used to handle loads of teak and firewood for the SJS network. Locomotives were fired with wood fuel as coal or coke had to be imported. The oil fields around Cepu produced a very good quality oil to be made into kerosene/benzine/white spirit with a little residue left, good for asphalt only.

In 1929 the forestry sidings were enlarged and a large saw mill erected. A weighbridge manned by an NIS employee was put in at Ngareng, two km from the exchange siding at Batokan on the forestry network, to weigh the wagons of sawn timber and firewood which had to be handed over, and to assess the charges.

The BPM built a new magazine and filling installations west of the SJS Cepu-Blora line, connected to the NIS line. These sidings were called New-Ngareng and were worked by a BPM-owned diesel-electric loco because of fire danger. The sidings at the oil plant were called Old-Ngareng. Thus rolling stock of four different concerns were at one time running over these lines.

On the 5th October 1914 a carriage for BPM employees' school children was attached to the relevant NIS convoy that ran from Cepu station to (old)Ngareng. On 1 July 1915 similar convoys handled BPM office staff four times a day. As the industry expanded, more people travelled and by 1921 three carriages were needed in the convoys to handle the numbers travelling. But a new quarter was built for Europeans, away from the railway line. The BPM then started to run a bus for the school children, bicycles became more affordable, and these passenger services were gradually reduced. The school convoys were discontinued after the Christmas holidays of 1933.

In 1923 the convoys for office workers were reduced to two carriages and in 1937 to one carriage and on the 31 May 1938 they were discontinued altogether.

Map of Cepu Area

The world depression of 1929 took effect and the technical supervising staff of Traction and Way and Works were withdrawn (or made redundant). The NIS workshop at Cepu had most of its activities transferred to Yogya Lempujangan, where the NIS had its main workshop already for both gauges.

My father was transferred to Surabaya, with his office at the NIS station at the suburb of Pasar Toeri (Turi), a neat and well-kept station.(Home station of NIS section b).

All NIS personnel had to suffer a cut in their salary or wages, initially of 10% in 1929, which was increased to a cut of 20 percent some months later. This depression hit hard in all sections of society and industry. The SJS had to go into receivership and remained as such till the Second World War. Many of the once busy sugar mills had to close production, thus considerably reducing the earning capacity of the tramway companies that did the transporting. Many people either walked or used the wild-cat bus services.

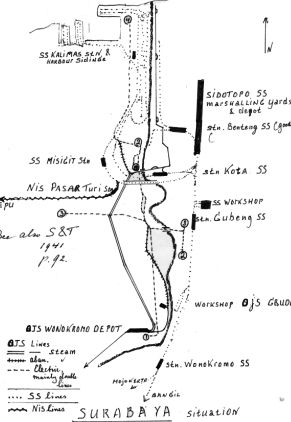

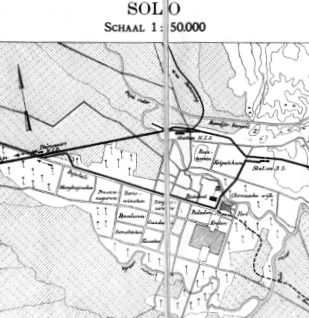

Surabaya has always been an export port for most of Eastern Java. Many private tramway companies served the export industry, mainly sugar, in East- and Central-Java. Surabaya was also the terminus of the OJS (Oost Java Stoomtram-maatschappij) and the SS(Staats Spoor - State Railway) which ran from Batavia, now Jakarta, to Surabaya via Yogya and Surakarta or Solo.

The OJS, an offshoot from the SJS, served Surabaya initially with a steam tram. The town line started at the mouth of the river Kali Mas on the eastern or right hand side of the river called Ujung. Here was the Harbour Master's office, a ferry terminal for the island of Madura across the strait of Surabaya, a navy establishment and warehouses along the canalised section of the Kali Mas. The SS goods yard from which sidings served the warehouses was located at a military fortress, called Prins Hendrik (now Benteng = Ind. for fortress).

The town line then went to the SS passenger terminal staton Kota, where a connection was made with the SS line. The town line continued then in a southwesterly direction across the Kali Mas and then south through the town along the streets and the west bank of the river to Grudo, where a workshop was built on the outskirts of town. From Grudo a country line continued for about 8 km to a sugar mill near Sepanjang. This was all established around 1890.

The OJS also had a steam tram line, which was separate from the town network, from Mojokerto to Ngoro with a branch to Dinoyo. This OJS country line served quite a few sugar mills and handed its loading over to the SS at Mojokerto for onforwarding to the port at Surabaya.

The town steam tramway was financially successful and by 1910 the company was considering electrifying the system, doubling the single line system, building a steam tram line around the built-up part for a goods line to a new development of the port on the western side of the river mouth, called Tanjung Perak. This goods line ran from the old town via Pasar Turi station along the western outskirts south to Wonokromo and joined there the country line. This was in place by 1916. This steam tram ran a passenger service which still exists and is a "must" for visiting railway enthusiasts.

The First World War delayed the electrification and as a first step a steam tram line was opened in 1920 to Tanjung Perak which junctioned off the goods line near Pasar Turi. In 1923 a connection with the NIS system was also made at Pasar Turi. During 1923, the OJS Surabaya electric tram system began operating. The route of the single line steam tram through the southern part of town to Grudo was then abandoned and an electrified double line took its place although following a slightly different route via the Palmenlaan (now Jalan Panglima Sudirman).

The OJS workshop at Grudo was at the end of a short line from Wonokromo where a new depot was built and the new electric tram line 1 through the Plamenlaan terminated. The steam tram through the western suburbs outlasted the more modern electric tram system by some six years until the early 1970s. It became in those years unique and often photographed.

Map of the Surabaya area

The main SS station was called Gubeng, from which the express trains leave. There is also Surabaya-Kota (town) station, located in the centre of the city. The main line of the SS came in to Surabaya on the eastern side of the river Kali Mas. Goods trains continued past Gubeng, the SS workshops and a junction to the Kota passenger station to arrive at the large marshalling yard of Sidotopo. Goods wagons for the eastern side of the river went then to the goods yard of Benteng.

Those for the western side of the river went back towards the Junction and took a high level line that opened in 1926 and crossed overhead a busy street at Pasar Besar, the Kali Mas and the OJS steam tram line Wonokromo to Ujung, to come down at the SS station Missigit. The NIS and OJS lines joined the SS lines at Misigit. The lines curved north here and crossed the OJS electric tram line to Perak, to finish in the goods yard of Kali Mass SS. From here sidings went to the new harbour basin and along the west side of the Kali Mas river.

On both sides of the canalised river Kali Mas ran a profusion of railway lines to the many Godowns (Gudangs). The area smelt strongly of sugar and molasses. My father had to go there at times to see Chinese traders regarding transport of products. I remember once when I came along, I was served a cup of green tea by Chinese traders.

I used to go to school by tram, taking line 1, which ran through the Palmenlaan (Jl. Urip Sumoharjo), a main thoroughfare, to the Darmo boulevard, from where it was a short walk to the Christian Brothers school. The trams were of the continental style, four-wheelers, painted a yellow-cream colour. They were built in Hanover (Germany). The trams had longitudinal seats and straps for standing passengers, and the floor was made of half inch slats.

The railway gauge is 3'- 6"(1067 mm) in most of Indonesia, except in the province of Aceh in Northern Sumatra (750mm) and in my time, the NIS line Semarang to the kingdoms (Native states) in Central Java. This system had 4'- 8-1/2" gauge (1435 mm) and was called the broad gauge (breed spoor), whereas the "standard" gauge of 3'-6" was called the cape gauge (Kaap spoor from the gauge in South Africa)).

The rolling stock of the SS and private companies was freely interchangeable. The standard 4-wheel goods wagon was 12 ton gross. There was a system of black circular markings at either end of the goods wagons to indicate the gross weight when this weight differed from the standard 12 ton.

Due to the tropical downpours, most wagons were of the closed type, four wheelers with a galvanised-metal body and a brakeman's seat on the roof. Depending upon the gradients, brakemen were used as labour was cheap then. The SS had goods wagons with little roofed-over platforms at one end for the brakeman.

Before the invention of the Vacuum brake and the Westinghouse brake systems, brakemen were employed by the railways all over the world. Depending on the weight of the train, the gradients and speed, all railways had regulations on how many brakemen had to be carried in each section of line. These men acted on the whistle signals from the engine driver to apply or release the hand brakes of one or more wagons, thus assisting the driver to control a moving train.

The NIS locomotives fired teak wood and this firewood was carried in four-wheel slatted wagons to the various loco depots. This firewood came from the boles left in the ground after the cutting of the trees in the teak plantations and from the off-cuts from the sawmills. The centre-buffer coupling, the chopper type, was standard on the cape gauge.

Passenger carriages were end-loading with open platforms, except on some expresses, which had carriages with closed-in platforms. The NIS had a good number of four wheel passenger carriages in use, mainly in the 3rd and 4th class. A feature of many trains and trams then was the "pikolan wagen" or "pasar wagen" (market wagon), in which travellers could place their (often) bulky baskets. The bulk of passenger travel in the Indies was in the lowest class over short distances and mostly with bulky goods.

Passenger rolling stock of the SS and SCS (Semarang - Cheribon Stoomtram-maatschappij) was painted teak or brown originally, while the other private companies generally used dark green. The goods stock was predominantly black or the grey of galvanised iron.

My father was transferred to the head office of the NIS in Semarang about the end of 1933. We travelled by train and I remember my first lunch in a dining car (nasi goreng or fried rice).

Our car, a huge old Fiat (the brand my father favoured all his life) was put on a flat car and came by goods train. The Fiat had a sailcloth roof which could be folded back. For inclement weather it had transparent mica panels to put in the doors. It had a horn with a rubber ball which one had to squeeze. When the Fiat arrived at the Semarang goods station of the NIS, I came along with my father and noticed the track and wagons being bigger on the other side of the goods platform. This was my first encounter with the "broad gauge" as it was called then.

The NIS built the first railway in Java in the 1860's. The line from the port of Semarang to Surakarta and Yogyakarta was built by the NIS to the European standard gauge in their new concession before the 1067 mm gauge was adopted in the colony around 1870. It gave the NIS a monopoly position for many years in Central Java, as in later years it effectively divided the SS system into an eastern and western region. The State started building railways in Java in 1875, beginning in Surabaya.

A condition of being granted the NIS concession in Central Java was building a railway from Batavia (Jakarta) to Buitenzorg (Bogor). This line was built to the cape gauge and sold later to the SS.

In later years, the government wanted to connect their two regions in order to run SS trains from Batavia (Jakarta) to Surabaya via Yogya and Solo. For through running, a third rail was laid in 1899 by the NIS between Yogya and Solo for which use the NIS was paid by the SS.

The third rail caused congestion in traffic and a separate 1076 mm gauge line was built next to the NIS line for the sole use of the SS trains during the twenties, opening for traffic in May 1929. It was called "vrije verbinding", literally "free connection". This line belonged to the NIS and the SS paid rental for its use.

The dual gauge line was then used by the NIS as it had built lines from Surakarta to Baturetno (1920) and from Jogya via Magelang to Parakan and Ambarawa in the 1067 mm gauge.

The NIS had also bought the Solo Tramway Maatscahppij (STM), which had a line running from the SS station at Surakarta (Solo Jebres) via the town (Kota) and Purwosari to Boyolali, using horse traction on the cape gauge. The STM was a simple but fairly profitable affair from all accounts and was bought because it had the concession to transport the export produce of the sugar mills along its line to Boyolali, which it handed over to the NIS at Purwosari for onforwarding to the port of Samarang. The STM crossed the NIS line at Purwosari.

It also operated a horse-drawn tram service in the town of Surakarta (Solo). The line was made suitable for steam traction after the turn of the century and taken over by the NIS in 1906. The reason the NIS opted for the 1067 mm gauge was that the Colonial Government had adopted this gauge as the standard for the Indies. Hence subsequent lines had to be built in that gauge, except for two tram lines south of Yogya, which were used to carry the export produce of some sugar mills in the area via the NIS broad gauge to the port of Semarang.

Thus when the NIS wanted to connect Semarang with Surabaya, it started from Surabaya and from a station on the broad gauge, Gundih simultaneously, with a cape gauge tramline via Gambringan-Kradenan -Cepu-Bojonegoro-Babat-Surabaya Pasar Turi.

As this line was then classed as a steam tramway, speeds did not exceed 45 km/h. In the early 1920s, the NIS then built a cape gauge line from Gambringan to Semarang to avoid the change of trains at Gundih. However the speed allowed on this line(30 km/h) was not very high and it was not till 1/5/1928 that through passenger trains started to run at a speed of 45 km/h. However traffic increased as passengers preferred the journey which did not require changing trains.

Previously one travelled from Semarang to Surabaya and return by broad gauge NIS Semarang to Solo, changing to the SS train from Solo to Surabaya Gubeng. The NIS connection from Gundih to Surabaya at first did not alter the changing of trains and speed of the journey. Competition with wild-cat bus services forced the government to raise this line to a railway of the second class in the depression years, and speeds were increased from 45 to 59 km/h in 1935. Work had then already started to make Semarang -Surabaya a first class railway on which speeds to 75 km/h were allowed. Trains started to run at this speed as from the new timetable of May 1937. Discussions started then regarding the use of diesel-electric passenger train sets.

The main workshop of the NIS, which catered for both gauges, was at Yogya Lempuyangan. Hence there were facilities at Gundih and Solo-Purwosari to lift locomotives and wagons of the cape gauge onto broad gauge transporters.

Cape gauge bogie rolling stock had broad gauge bogies fitted for this transfer. In late May 1940 a third rail was ordered to be put in between Gundih and Solo for strategic reasons. This dual gauge line was ready for use by 1 August 1940.

The broad gauge is gone now. The Japanese occupying power, with no monetary or legal constraints about concessions and agreements, converted the broad gauge to the standard cape gauge during August/September 1942. The broad gauge between Semarang and Brumbung was lifted entirely and the single cape gauge line of the NIS replaced this traject. From Brumbung to Gundih and from Kedung Jati to Ambarawa, one rail was brought closer in to the cape gauge. From Gundih to Solo and Yogyakarta the then dual gauge was reduced to cape gauge by lifting one rail. The cape gauge line that ran next to the dual gauge between Solo and Yogyakarta (the vrije verbinding) was also lifted.

The Japanese shipped the broad gauge rolling stock of the NIS to Manchuria where it was useful to the Japanese occupying power.

To assist the allied war effort in the Middle East, some 80 broad gauge wagons had been sold to Egypt during 1940. These were seemingly no longer required because of the downturn in sugar exports after the depression of the early thirties. Before the depression, there had been large volumes of sugar exports to British India until it started its own sugar industry.

The broad gauge was always an impressive sight to someone not used to the larger gauge. To a boy like me, the locomotives, carriages and wagons were all so huge with their screw couplings, compared with the cape gauge with its chopper coupling and safety chains.

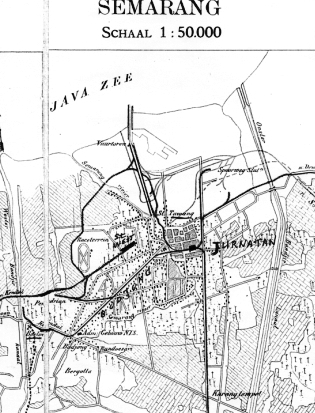

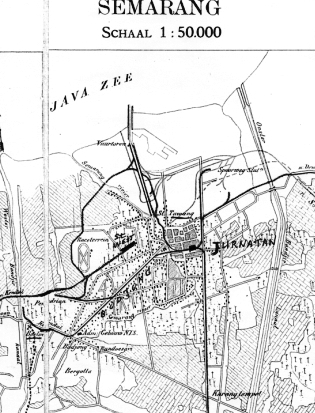

Semarang

Semarang is the capital of the province of Central Java. It is a port with a roadstead, hence lighters brought the export produce from the godowns to the ships lying in the roadstead.

The main station of the NIS was Semarang Tawang, a terminal station for both the broad and cape gauge of their passenger trains. It became the central station of Semarang after 1942. When Tawang was opened, the original terminal station of the NIS broad gauge in Semarang became the goods station from where lines went to the port.

Semarang Tawang station was a large roomy building on a square at the edge of the older quarter of the city. In the square opposite the station stood (then) like all over the Indies a long row of "dokkars" (dogcarts - a two-wheeled vehicle pulled by a horse). My father had an office there at one time. I was much intrigued by a contraption that was run by a clockwork motor and in which a jam-coated roll slowly turned into a cage, catching the flies that were sitting on the roll. On my father's desk was a large array of safe-working signs, all with chrome-plated handles, which I think were used for classes and exams.

The main platform was served by a broad gauge line with a run-around loop. The third line was dual

gauge and served an island platform, with access on the level. On the other side of the island platform

was a cape gauge line. These latter lines were put in after the NIS cape gauge came to Semarang from

Gambringan during the twenties. Trains were made up at the old NIS station and set back into the platform

before leaving. Similarly, a terminating train reversed to the old station yard when it was finished.

At the old station yard, there were loco facilities, a workshop, goods shed and marshalling yards for both

gauges. The workshop was the original broad gauge workshop of the NIS before the opening of the main workshop

for both gauges at Yogya Lempuyangan.

Lines ran from the old NIS station yard to the port of Semarang on the east side of the canal, a broad gauge line crossing the canal by a draw bridge. The cape gauge on the west side of the canal was served from the SCS line at Poncol.

The port of Semarang, like Surabaya, developed along a canalised river, the Kali Semarang. Wharfs and godowns, served by road and rail, were erected on both sides of the river. As the draught of ships increased, they had to stay in the roadstead and transfer of loadings was done by lighters. In Surabaya, a deepwater port was then built next to the navy establishment.

In Semarang a pier stretched out into the sea. There was also a harbourmaster's office, a waiting shed for passengers, and customs facilities, called the "kleine boom". There was a harbour basin here for shallower draught ships and lighters, served by rail.

There were always ships in the roadstead, many of the Royal Dutch Packet (KPM - Koninklijke Pakketvaart Maatschappij) and its subsidiaries, one of which was the JCJL (Java-China-Japan-Line). The KPM had freighters going all over the archipelago, to the most remote places. This company also had regular liners running almost to a timetable between Australian ports, Java, the Straits Settlements (now Singapore and Malaysia) , Sumatra, British India and South Africa. These white ships with yellow funnels, such as the "Melchior Treub", "Maatsuycker", "Van Heutz", were all named after former Governor-Generals of the Indies. These ships were floating hotels, in which one travelled overnight from Semarang to Tanjong Periuk to catch the weekly liner to the Netherlands. The story of these ships has been the subject of a number of books.

Three privately owned railway companies worked from Semarang. The Samarang-Cheribon Stoomtram-maatschappij (SCS) went west to Cirebon. It was a company that was called Stoomtram (steam tram) yet it had the status of a first class railway, and in later years had through carriages from Semarang to Batavia (Jakarta), which were handed over to the SS at Cirebon. To balance out running costs, the through carriages were supplied by both the SS and SCS.

The SJS went Northeast to Rembang and the country beyond and to Cepu. It was the oldest private tramway company and started off as a town tramway in Semarang.

The NIS, both cape gauge and broad gauge went east and south, the cape gauge going to Surabaya and the broad gauge to Surakarta (Solo) and Yogyakarta.

Near the NIS goods station was a connection with the SJS network to its city station at Jurnatan. Jurnatan station was the beginning of the SJS country services but also the city station for its town lines. It is a bus station now (1995) but in its days was an impressive station, completely roofed over, with four lines and busy with trams running all day, and changing and servicing engines. The engines were small 0-4-0's with enclosed motion made by Beyer Peacock hauling generally two bogie carriages. Lines went from Jurnatan to Jomblang, (4,5 km, opened 1 Dec. 1882), Jurnatan - Bulu, along the main street, Bojong, (3 km, opened March 1883 and extended with another 800 m in 1899 to the Wester Bandjir kanaal). (Bandjir = flood i.e. overflow canal).

There was also 2.5 km from Jurnatan to the Kleine Boom open in July 1883. The SJS goods trams used this to the port but in later years, to avoid the city centre, these goods trams used the NIS connection to the port.

As it was, any NIS and SJS loading for the western side of the canalised Semarang river had to come through Jurnatan to go part of the way along the Bojong where the goods convoys turned off into the Genielaan to Pendrian. At Pendrian, the trams reversed and went via the SCS station at Poncol over SCS lines to the west side of the river. This situation arose after the development of the western side of the canalised river, and before the SCS had made its own terminal at Poncol.

Originally the SCS used the Djurnatan station as its Semarang terminus, whereby its trams had

to run along the town streets to finish or start their journey. The new SCS station was built on

the same axis as Tawang. A kilometer of town area separated both stations, causing the reversing of

goods trams at Pendrian.

This was all single line with crossing loops for the passenger trams at stopping places.

The town passenger service closed on 1 March 1940.

The goods trams through the city were hauled by SJS engines of the 0-6-0T type. One could see vans from up to half a dozen companies in the make-up of these trams.

The SJS, SCS, OJS and SDS (Serayu Dal Stoomtram-maatschapij) were grouped in a "sister" company with a universal workshop in later years to rationalise building and maintenance.

The broad gauge reached the west bank of the canalised river via a draw bridge.

Semarang was protected from a flooding Semarang river by the East- and West-banjir canal (banjir = flood[Mal.]), an overflow system regulating the flow in the river through the city. A similar overflow system protected Surabaya from floods.

Map of Semarang situation by 1939

During 1940 the SCS terminal station Semarang-West or Poncol was connected to the NIS Semarang- Tawang and Tawang then became then the central station for Semarang. This enabled trains to run from Jakarta to Surabaya along the North Coast, shortening the distance and avoiding heavy grades in the mountainous backbone of Java.

In Semarang we lived in Kintalan Lama, where there were houses for NIS employees.

With my brother Henk, I explored around the Kali Semarang on the bank of which ran a 60 cm gauge line for about 3 km. This line belonged to a Chinese firm dealing in sand and gravel at Bulu. The office and storage yard were on the road to Tegal and near the terminus of the SJS Town tram in Bulu. In the storage yard there were some curved sidings where the different types of river gravel and sand were dumped. This material was brought in by little trains of four tip trucks, pulled by a span of oxen. The line went through a kampong (native quarter) behind the storage yard, crossed the Semarang river at the Weir with the Wester banjir canal and then followed the river bank for a further 2 km to a site in a bend of the river where a lot of sand and gravel were deposited. There was a crossing loop half way down this line but it was rarely used.

The driver of an empty tram would simply steer his oxen span to one side of the line and derail the four trucks clear of a full tram. When the full tram had passed, the oxen pulled the lot back on to the line again and the driver assisted with a long pole in rerailing the trucks. We hitched many a ride on those little trams.

Another dangerous exercise was to sit in between the flanges of the bridge girders of the SCS line across the Wester banjir canal as a train came across. It was very common in the Indies for pedestrians to use the railway line and bridges.

It was around 1934 and I was nine years old then. My father was due to go on furlough after six years service with the NIS. Prior to embarkation for the Netherlands, the European employees were posted to Semarang Head Office.

We left soon for a holiday in Holland, but apart from some dockyard railway scenes at Tanjung Periuk, Singapore, Belawan Deli, Colombo, along the Suez canal, Marseille, Algiers, Tanger and Lisbon, I do not remember much. We arrived in Rotterdam and I remember seeing the first streamlined diesel train between Rotterdam and Dordrecht, when sitting in the train to Eindhoven, where my grandfather lived. As mentioned previously, my grandfather had been a signalman in the signalbox of Eindhoven station.

The railways in the Netherlands were mostly steam in the 1930s. There were still plenty of three-axle carriages used in passenger trains, some without lavatories, even on long distance runs. I well remember one evening on a non-stopping train between Zwolle and Amersfoort, where we had to change trains, that I had an urgent call of nature and had to squat down on the floor when coming into Amersfoort!!

I was very much taken with a shunting motor, that was recently introduced by the Netherlands Railways and was called a "sik" (billy goat). This one shunted intermediate stations and collected goods wagons. These wagons were later made up in goods trains at a bigger station. As my meccano set had four flanged wheels, I attempted to make a model of it, while staying with the family in Wolvega, where I saw this engine in action.

In Eindhoven we took long walks with my grandfather, mostly in the heather country along the road and railway line going north to Den Bosch. Blackberries grew in profusion along the railway embankment. One day I saw a long goods tram of the Brabantse Buurt Spoorwegen (BBS) coming from Son, crossing the main road, at what was then the outskirts of the town, to go underneath the railway and then follow it into Eindhoven. It was many years later that I learned how this BBS concern arose from the various tramway companies in Brabant and was at the time changing over to busses. It must have been one of the last goods trams that I saw.

At that time the motor car was ascendant and in and near the larger cities the railway lines were raised to avoid level crossings. Thus I have known the situation in Utrecht, a most important railway centre in the Netherlands, with a street crossing just west of the platforms there, the Leidse straatweg. One can imagine the barriers being down most of the time there. A pedestrian underpass was already in use.

It was the same at the crossing of the Amsterdamse Straatweg with the busy double line to Amersfoort. We went frequently along this street, mostly by electric tram on line 2, to family that lived in a suburb nearby.

The station building in Utrecht was already out of date then and it would burn down a little later. The next building also burned down and nowadays one can hardly imagine what it looked like then. The station restaurant in the waiting rooms at Utrecht served a very good Indonesian nasi goreng (fried rice) in the years before the Second World War. Apart from some places in The Hague (and perhaps Amsterdam and Rotterdam), one could not get this kind of food in the Netherlands then. Contrast that with now (1995) when every little village in the Netherlands has its Indonesian restaurant.

The square in front of the old railway station was full of trams. There was the interlocal

tram to Zeist with its double collectors, so as not to cause electrical interference with the

instruments at the Royal Metrological Institute along its route at De Bilt. My acquaintance

with this system was to come later.

And there were the city trams, which were to disappear

in 1938, to make way for buses. The tram depot was near where we lived, at a powerhouse on

the Catharijne Singel.

At the depot, there were some curious vehicles, used in maintaining the tramlines, such as railcleaners, railgrinders and watersprinklers.

The system sold a dayticket for 25 cents and I was occasionally given such a ticket, no doubt to keep me quiet, and I travelled all over the system. The lines to the newer suburbs had quite modern rolling stock, large four-wheel motorcars but in the narrow streets of the innercity, a smaller motorcar was used. The livery was yellow. One tram line ran underneath the tower of the Dom, a most curious sight. This tower was the highest in the Netherlands at the time and open to the public. This Dom tower belonged to the cathedral church of the Arch Bishopry of Utrecht, a very old Bishopry in the Catholic Church. The centre part of the Cathedral nave had collapsed and was never rebuilt. The area was made a square between the Dom tower and the back part of the cathedral, which was still large enough to be used as a church. A junction of the tramlines was in this square.

Utrecht station is the place where one can frequently see three trains leaving simultaneously in the directions of Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Amersfoort. In the days of steam this was most impressive.

When my father's furlough was over, he went ahead of us back to the Indies. Hence when we returned to the Indies on the MV "Johan van Oldebarneveldt", we did not often disembark the ship as my mother had her hands full with four children. Aboard this ship I saw for the first time a Hornby double O set, which was something new then. It was owned by an English boy who came aboard in Southampton.

My father was promoted to Superintendent Movement & Commerce (Inspecteur Beweging & Handelszaken) (NIS section I) and was allocated an office in the Head Office of the NIS at Bojong in Semarang. We went to live in Candi Baru, the Parallel weg (then).

As long as I can remember and for my whole life I have had a train set. Before we went to Holland, these trains were mainly of Japanese make, just a circle with a little loco, tender and a few carriages, which one got from Sinterklaas (Dutch Father Christmas) or on a birthday. Generally the spring broke fairly quickly or wheels came off and went missing. From Sinterklaas in 1934 I received a loco, tender and some carriages with rail, all made by Märklin in O gauge. The firm Märklin of Nuremberg in Germany still makes trains, but no longer in 0 gauge. The boy next door in the Parallel weg had a I gauge train, which took my interest then, but it was almost sixty years later until I began collecting that gauge. For most of my life, I collected O gauge. There was a shop in Semarang that sold Märklin, and big live steamers in gauge 1 and even 2 were on display but out of my financial reach.

My father was appointed to the NIS section II, homestation Surakarta (Solo) and had his office at Solo-Balapan, The house that went with the position was in easy walking distance of his office.

In the 1930s, the world depression hit the State Railways and the private railway and tramway companies in the Indies severely. Private motorcars and wildcat omnibus services competed with the railway passenger services. There were no regulations or acts to keep road transport in check. At the time this situation was the same all over the world. Lowering passenger tariffs, more frequent and faster services were used to combat the road competition. Many mixed trains disappeared. In their place came separate goods and passenger trains.

On its most popular routes, the SS started running light trains at high speeds more frequently through the day. The NIS also increased the speed and frequencies of its trains. Passenger rolling stock were made more comfortable and brighter. In first and second class, air cooling was installed and there were early experiments with air-conditioning. The bogies on the passenger rolling stock were made suitable for higher speeds.

Thus on the broad gauge, five fast passenger train services each day were begun in each direction between Semarang-Solo-Yogya. These trains stopped only at a few intermediate stations.

The carriages were modernised and the enclosed balconies were given a stream-lined appearance. The fixed windows in the second class were enlarged and green-tinted glass was installed to keep out the heat of the sun. The first class had been abolished on the broad gauge by 1938. The air flow into the second/third class carriage was filtered and directed over ice blocks. The fourth class carriage and brake-van remained the same but for the altered balconies. This rolling stock was painted a light shade of green with cream uppers similar to the SS fast trains and the trains on the NIS cape gauge. The locomotives were painted the same shade of green all over.

These new fast trains were quite a success and I had a few trips in them between Solo and Semarang on our family pass.

In NIS Section II were two native States, the Sunanate ruled by HRH Paku Bewono X (PBX), the senior member of the House of Mataram; and the Mangkunegaran, a distant relation of the house of Mataram, whose ruler was called the Mangkunegoro. There was a similar arrangement in Yogyakarta (the Sultanate and the Paku Alam, both of which were also branches of the House of Mataram).

The Indonesians venerated these rulers with almost religious fervour and when these kings travelled about, there were always great concentrations of people making obeisances to them, squatting down and putting their fingertips together in front of their face (Sembah).

These rulers had their own armies, modern rifle detachments and old fashioned detachments, equipped

with bow and arrow, lances or muskets and clad in armour. These detachments were used for guard duties

and ceremonial occasions. Court etiquette and "Adat" (conduct in the presence of the ruler) were rigidly

observed. My father, as the NIS representative, had to attend court many a time.

The Dutch civil

government was headed by a Governor, who had a half-squadron of cavalry and an infantry company as his

military arm.

At that time a change of Governor-General (GG) took place and the native rulers all travelled to

Jakarta to welcome the new (and what proved to be the last) GG. For such an occasion, PBX travelled

by special train, accompanied by his retinue and state sacred objects and jewellery.

The Mangkunegoro

travelled in extra carriages attached to the prestigious "eendaagse" (an SS express train that ran during

the daylight hours from Surabaya to Jakarta via Solo/Yogya).

The GG then made then a return visit, also by train. These train trips required elaborate organisation. For the GG's visit, a special protocol book was issued, which laid down all the proceedings for both halves of the return journey, including where the train had to stop, who had to be on the platform to greet the GG, the order of the processions to the Kraton (palace of the ruler) and the Governor's palace, and the timings of the events.

All along the railway lines travelled by royalty, there were huge movements of people by rail in extra trains. Extra trains were put in to move large contingents of military from distant garrisons to line the route of the procession.

Solo-Balapan in those days was rather ornate, as the native rulers frequently used it for their travels. There was a large square in front of the reception building, and a huge, roofed-over crossing on the level of the cape gauge lines of the SS that brought one to the station itself on an island platform. On the other side of the platform, the northern side, was the broad gauge. The line from Semarang came in from the East and went on to Yogya. The SS line from the East came from Surabaya and Solo-Jebres and went also to Yogya via the "vrije verbinding"

The station itself had a royal waiting room and on big occasions the red carpet was laid out.

Between Solo and Yogya there is fertile country producing sugar cane (with many sugar mills) and also a particularly good tobacco leaf which was much in demand by the world's cigar manufacturers as a wrapping leaf ("dekblad").

The broad gauge line had a third rail between Solo and Yogya (dual gauge) and there was also a cape

gauge next to it for the use of the SS trains (Vrije verbinding). The dual gauge was used then by the NIS.

From Solo Balapan going to Yogya , the first station was (Solo)-Purwosari. The "vrije verbinding" went

along the South side of the railway yard. The dual gauge had a platform and station building for passenger

traffic, and the railway yard was in both broad and cape gauge. There were lifting facilities for piggy-backing

rolling stock to and from Gundih, for which different kinds of transporters were available, such as a

twelve-wheeled vehicle to carry cape gauge locomotives; and a three-axle wagon that carried four-wheeled

vehicles in the cape gauge and broad gauge bogies and which could be fitted underneath cape gauge passenger

vehicles. For the latter, there was also a special coupling arrangement available to match with broad gauge

rolling stock. This was prior to 1940.

Two cape gauge NIS branches went out from Purwosari, one to Boyolali, serving sugar mills. The branch was originally built by the Solo Tramway Co. and bought by the NIS.

This line went through Javanese countryside at its best, the heartland of a native State, terraced rice fields (sawah's) up the mountain slopes, small villages (dessa's) everywhere. Nearby Kartasura, a station on this line, there were the ruins of the old Kraton, the royal residence, before the court moved to Solo.

On a visit to Boyolali to the Regent (the highest native civil servant) with my father, this gentleman gave me the nail of a tiger he had recently shot.

Solo Area

The other branch line went to Baturetno. It crossed the broad gauge, the "vrije verbinding" and a main road on the level and followed this road as a town tramway into Solo, past the Kraton, to a station Solo Kota(town). Here it went on its own formation to Wonogiri and Baturetno, where there was a Japanese-owned copper mine which generated some traffic. The line was also used to transport gaplek, a product from the cassava root and other local produce. This branch was rather new, being built in the early twenties.

The section from Purwosari to Kota was formerly part of the Solo Tramway Co. and was worked by horses till about the turn of the century. In the town it turned into the Chinese quarter and went to the SS station at Solo-Jebres, but this part was abandoned by 1914 following the sale of the Solo Tramway Co to the NIS.

On important occasions at the Kraton, such as Pasar Malam (a type of fair) and Islamic religious festivities, when there were many people about, train traffic between Purosari and Solo Kota was halted. It was an agreement that trains came to a halt when a procession was in progress.

I went quite often with my father on his inspection trips, mainly by car, although once by train to Wonogiri. My father had to scold quite a few stationmasters along the line as the trains were often delayed by too much socialising of station staff with train crew, indulging in iced tea together.

In contrast to the other lines of the NIS, where the safe working went by railway telegraph, the lines taken over from the Solo Tramway Co. were worked by telephone.

Nowadays with sophisticated electronic systems in use, it is difficult to realise how the morse telegraph system worked in conjunction with the safe working of trains on single lines. For a start, the operators had to qualify in the morse code, where a system of dots and dashes represented the letters and numerals. A wire between the stations carried the electric impulses of the dots and dashes, with the earth used as the return. A switch, called the morse key, was used to make the dots and dashes impulses and at the receiving end, these were printed on a long, thin band of paper, the ticker tape. Thus train orders were sent.

There was also an extensive vocabulary of words covering all business that could arise at a station, covering not only safe working of trains, but also relating to loadings, availability of wagons, seat and berth reservations, personnel management and many more matters. Once a day the standard time signal also came through, whereby the station clocks and watches were set.

Experienced operators could listen to the clicking of the telegraph and jot down what was being sent.

As mentioned previously, many pedestrians used the railway lines and especially the railway bridges as short cuts. I accompanied my father once to a fatal accident, where a deaf woman was caught by a train. There was not much left of the poor woman. A policeman was gathering the remains, just a pathetic small heap of flesh. A few times I saw very near misses on the long railway bridge crossing the river near where we lived, when people could only just make it to one of the pylons and safety.

Continuing from Purwosari towards Yogya there were crossovers at a few stations between the track of the "vrije verbinding" used by the SS and the cape gauge of the three-rail NIS line, at Delangu, Klatten and Brambanan. These could be used if one line was blocked for the cape gauge trains.

The Dutch "Controleur"(civil government official) of Klaten had a huge Märklin layout in O gauge, which I went to see. In the broad gauge train on the way home towards dusk, the train conductor asked if I wanted to travel in his van in the cupola overlooking the whole train. I could see the loco spewing out lots of sparks from the chimney in the gathering darkness. There was no night time running in the Indies until the introduction in the latter half of the thirties of a night express from Jakarta – Surabaya and occasional specials to sporting events in Surabaya.

With some savings and a lot of pestering of my parents, I got an O gauge electric train set of Japanese make, a 2-6-0 loco with 3-axle tender and three bogey carriages all of Japanese outline. The Japanese O gauge was 2 millimetres wider than the European O scale apparently, as I had to wind a bit of thin copper wire around each axle of the other rolling stock I had at the time, to make the wheels stay out a bit wider. Later on, I got two points as well to make running a bit more interesting than just on an oval. This train set, as well as rolling stock made in tinplate by various makers, was reasonably cheap at the time. And wasn't the lithographed tinplate realistic! Stupidly I sold the lot during the Second World War.

Once in this district my father had to contend with a huge washaway, in which the dual gauge line and the line used by the SS were hanging in the air. My father was some 27 hours on the spot organising the repair and continuation of the service. In the Indies. with its sudden and huge rainfalls causing raging torrents in rivers called banjirs, spare bridge components, sleepers and ballast were kept in reserve, especially near known trouble spots.

Early in 1938 my father was transferred to section IV with the home station at Magelang. Section IV ran from the home signal at Yogya to Ambarawa, which included the only rack railway in Java and a branch from Secang to Parakan. A road freight service of the NIAB, a company's offshoot, from Parakan to Wonosobo was also included in this management.

Accompanying my father on an inspection by car to Wonosobo, I saw a train of the Serajoe Dal Stoomtram (SDS) once. The loco had four coupled axles with a very long wheel base. I found out later that this was one of the SDS 201 - 205, with a wheelbase of 6900 mm and using Klien-Lindner axles. In this type of loco, the first and last axle can set themselves to sharp curves and at the same time such a loco is very easy on bridges, because the load is so spread out.

Magelang is a town which lies in a valley among the mountains Merapi, Merbabu, Sumbing and Sundoro. The Merapi is a very active volcano. Magelang was a garrison town, the base of an infantry regiment with a school for Warrant Officers. During the yearly military exercises (Manoeuvres), long military trains came and went through town. This special traffic, as in the other districts, had the closest attention of the various Superintendents, to ensure that rolling stock was available at the right time and place and that civilian timetables were not unduly obstructed by these extra trains with their sometimes unusual places of loading or unloading.

Magelang is laid out on a South-North axis, and the first station was Magelang Pasar (Market). Although there was a substantial building here for the considerable market traffic, the track was just single. The line then went through the main street of the mainly Chinese business quarter to come to a halt called Aloon -Aloon.

The Aloon-Aloon is a square which one finds in most towns in Java. Along its four sides were the town’s most important hotel, government offices, a mosque, a Catholic and Protestant church and the official residence of the Regent, called the Pendopo.

The line continued through the main street of the European quarter, past the entrance of the military barracks and into the yard of the main station, Magelang Kota. My father’s office was in the yard grounds.

In the grounds there was also a workshop where concrete paving blocks were made. The NIS at that time was experimenting with a better road surface between the rails of the track through the long main street of Magelang. The practice had been to use asphalt up to rail level with a groove for the wheel flange, but due to iron-wheeled road traffic and movement of the track bed, the asphalt was always breaking up. Thus the line was relaid in stages on a ballast of coarse river sand and concrete block sleepers. The space up to rail level was then paved with these concrete pavers, there being a suitably shaped paver for the wheel flange. To harden the concrete pavers, they were immersed for a period of time in a bath at the workshop, before they were laid in the road.

Just outside town was a huge government-run psychiatric hospital. In Magelang there was also the huge "Pa van der Steur" orphanage. The boys from the orphanage who were learning trades went by train every day to Yogya to a trade school there. This school traffic was at times trying to the railway personnel. Once, a few boys who didn't have their tickets with them travelled on the roof. After a while they got bored and stood up, and were swept off the roof by an overhead obstacle.

The branch line Secang-Parakan goes into the saddle between the Sumbing and Sundoro mountain. The climate is very bracing and the NIS has a beautiful guesthouse at Temanggung. The guesthouse was used by the higher grade personnel of the NIS. Once a year there was a gathering of all the executives of the NIS there also. The grounds in front of the hotel fell away down to a mountain river and to the right was a huge railway bridge on the Secang-Parakan line. The scenery was Java at its best. This line has since been removed.

The line Secang-Ambarawa has a rack section to overcome the saddle between the Sundoro and the Merbabu mountains. The locomotives were built by Esslingen. There is an 8 km rack section here, with Bedono at the summit. From Gemawang (on the Magelang side) to Bedono is only a short rack section, circa 2 km, but from Bedono to Jambu is approx. 6 km. It is then another five kilometers to Ambarawa, called "Willem Een" by the NIS (named after a nearby fortress called after (Dutch) King Willem 1.)

Gemawang and Jambu are simple crossing loops with Gemawang having a short siding to a one stall loco shed. At Bedono is a nest of sidings and a turntable to turn the rack locos as these always have to be on the down side on the haul between Bedono and Jambu.

My father managed to get the carriages up front if we travelled on the rack, so we could stand on the balcony. The locos approached the rack section at about 5 km/h so the pinion wheel could engage with the rack, which is sprung for the first few meters so the loco pinion can match with the rack. On long trains, a rack loco was placed in the middle of the train also.

In Ambarawa at the PNKA's railway museum, one rack railway loco is still kept with a few four-wheel carriages to be hired out on tourist trips as far as Bedono. The locals use the rack to run their little trolleys on. I saw this on a video sent to me by a friendly railway fan (1993). My brother Henk made a visit also to this museum and to Bedono in 1989. The line from Yogya to Bedono and the branch to Parakan are all closed now.

In 1939 Ambarawa station was an island station. On the western side of the platform was the cape gauge, on the eastern side was the broad gauge, and the end of the branch line from Kedungjati.

Nearby was also a huge swamp (Rawah Pening), drained by the Kali Tuntang. A huge dam in this river near Tuntang provided the water power for the hydro-electric works there. It was part of the concession for building the broad gauge from Samarang to the Kingdoms to build this branch (Kedungjati-Ambarawa) to provide transport for the garrison at Willem Een. When the powerhouse was built, the railway transported all the materials and there was a siding at Tuntang that led to the very steep incline to the powerhouse deep down in the valley. Heavy machinery could be lowered (or lifted) on the broad gauge railway wagon via this incline by a cable.

This broad gauge branch started from the junction station Kedungjati, which, as the name already implies (Mal. jati = teak) lay amid teak forests. It was a station on the mainline from Semarang to the kingdoms.

The barracks at Willem Een were used by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945 to house European women and children in the infamous women’s camp of Ambarawa.

NIS section III had its office at Yogya. This section comprised a broad gauge line from Klatten to Yogya and two branches with the status of tramway to Brossot and Pundung serving sugar mills in their area. These branches are 28 and 27 km long respectively. They curved away from the mainline in a southern direction around the town. About 1 km from the station Yogya Tugu, there was a junction of the two branches. The branch to Pundung goes past Kotagedeh, now a suburb of Yogya.

On the 22 February 1939 a special broad gauge funeral train ran from Solo Balapan to Kotagedeh conveying the remains of HRH the Susuhunan of Solo, PBX. The train consisted of three luggage vans for the wreaths, the hearse, and twelve carriage of three classes for the mourners and court officials. Millions of people travelled from all directions to stand along the line this train travelled, some 80 km. At Yogya the train was split in two for the two sections to proceed to Kotagedeh, where the coffin was brought to the local mosque to stay overnight. The next day the burial took place in the mausoleum of the Kings of Mataram nearby in Imogiri.

My father had just acquired a 8mm movie camera and I still have his film of the funeral train and the procession at Kotagedeh.

At the end of 1939 my father was due for furlough in Europe again. As I was due to start high school in Europe at the end of August, our family went ahead of my father to Europe to spend the summer there. I travelled ahead to Semarang by train while the family came by car. By then we had a new Fiat 1500, bought in Solo in 1937. As the train started to climb out of Secang, I looked back towards Magelang and had a feeling I would never see this again.

I left my faithful dog "Juno" behind after some four years with a Mr. Chevalier, who ran the local cordial factory in Magelang. Mr. Chevalier was a veteran of the French army in Salonika during the First World War under General Franchet d'Espery ("Desperate Frankie!"). Juno wouldn't take to anybody else and in the long run had to be destroyed I was told.

In Semarang I stayed with Tante Okki, a friend of my mother, who was a nurse. When I arrived at Tante Okki's place I was told she had gone, and friends of Tante next door took me in. He was a police inspector in Semarang. A Mr Jansen, who used to be the chief Stationmaster in Semarang Tawang, had gone as Stationmaster to Cepu. There his wife died and Tante Okki went to Cepu to look after him. Tante subsequently married him. Hence I arrived at a closed door.

My family arrived a day later and we stayed in the Hotel “Du Pavillion” in Bojong, pending the departure of the KPM ship "Melchior Treub". The transfer from the Kleine Boom to the ship in the roadstead by launch was a thrill, the small launch bobbing up and down in the swell and the prospective passengers trying to jump from the launch onto the bottom of the gangway of the big ship. Stewards were on hand to help people. We must have eaten something bad because the next day we were all affected by a stomach complaint.

We arrived in Tanjong Periuk, harbour basin 2 and were transferred by launch to basin 1 where the mail steamers left for the Netherlands. We were travelling on the MV "Indrapoera" of the Rotterdam Lloyd line. We had a run into Batavia (Jakarta) with an electric train from the SS, which ran a suburban service here from the harbour to Bogor. In those days there was also an electric street tramway system, which employed a gauge of 1188 mm. This street tramway system was originally run with fireless engines, but that was before my time.

The departure of the weekly mail steamer was always a big occasion. Boat trains ran to the quay from which the ship left. Leaving in the afternoon, an overnight sail made a morning arrival in Singapore, where we passed the huge battleship "Malaya" lying at anchor in the roadstead. At the dockside I looked at the, to me, quaint- looking rolling stock of the "Federated Malay States railways" (the FMSR, metre gauge).

Another overnight sail brought us into the harbour of Belawan Deli on the island of Sumatra, where we took a train to Medan for a drive around in a taxi. I thought the station here was very modern with a pedestrian tunnel to the island platform, which I hadn't seen before in the Indies. I also took a picture of a 2-4-2T, which the private Deli railway company (DSM) had acquired from Germany, built by Hanomag in 1928, nos.10583 -10585 and in 1929 10648 - 10654.

Sumatra had three State railway systems, two in the cape gauge and one in 75 cm gauge in the north of the

island in the Aceh province. The cape gauge systems were in the South of the island and from Padang in to the

mountains. The latter served the Ombillin coal mines and uses the rack on their steepest lines.

The private

Deli Spoorweg Maatschappij (DSM) had some 550 km track in the cape gauge and served flourishing plantations in

tobacco, rubber, tea and palm oil, transporting their products to the port of Belawan Deli.

Then it was onto Sabang on the island of Pulau Weh on the northern tip of Sumatra, which was then a coaling station, situated in a beautiful horseshoe shaped bay. The coal used to come from Padang on the west coast of Sumatra to fuel the steam ships.

The next port of call was Colombo where the ship stayed in the middle of the harbour basin. A large barge was put next to the ship and launches ran from this barge to the quay. Boatmen came out to sell souvenirs, mainly carved black elephants in all sizes, models of the local sailing boats and precious stones. I managed to see a tram here and Sikh soldiers exercising near big guns looking out over the sea. We also saw a snake charmer in action.

Then we sailed on past the island of Socotra, Cape Guardafui, the Strait of Perim, the Red Sea, Suez and the Canal where we occasionally saw the white trains of the Egyptian Railways going past. In Port Said we went to the shop of Simon Artz, which opened in the middle of the night when the ship came in. The early morning was oh, so cold there in our tropical clothing. Then we sailed past Crete, through the Messina Strait and past Stromboli.

Nearing Marseille, we saw a large number of French navy ships on exercise.

We disembarked at Marseille

and got a 2nd class compartment in a PLM coach of the ”Lloyd Rapide”. Our luggage fitted nicely in between the

seats and made a nice bed for all of us to stretch out on.

Just out of Marseille I saw a local train made up of three-axle side-door stock. In Lyon we saw huge numbers of French soldiers on the platforms. Signs of war! We shunted around Paris in the middle of the night. We were unaccustomed to people travelling right through the night like they do in big countries like France and Germany. In the Indies before the Second World War, rail traffic ceased by nightfall and it was only a night express of the SS that ran between Batavia(Jakarta) and Surabaya in the last few years before that war. In the Netherlands too, there were no passenger trains between midnight and five in the morning.

Early the next morning we were hurtling along near Antwerp and saw people picking vegetables for the markets bending over their tasks in the morning mists. The Lloyd Rapide (similar to the Nederland Express to/from Genoa) had no border controls in France and Belgium till it reached the Dutch border station of Roosendaal.

These boat trains were organised in the late twenties by the two Dutch shipping companies to expedite travel to the Indies, cutting travelling time to 3 weeks by ship from the Mediterranean ports of Marseille and Genoa. This overnight journey also avoided the long haul around the Iberian Peninsula and the crossing of the notorious Bay of Biscaya. It enabled the travellers from the Indies to stay some six days longer in the Netherlands. Tourists to and from the Mediterranean took the spaces then vacated by the travellers to the Indies.

The trains ran fortnightly. One week the Rotterdam Lloyd (RL) ran from The Hague to Marseille (and return) via Paris, Brussels, Antwerp to The Hague with rolling stock supplied by the French railway company PLM and the Wagon-Lits (CIWL). In the alternate week, a train ran for the Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN) ran from The Hague, via Utrecht, Arnhem, Cologne, Mainz, Basel, Luzern, the Gotthard, Milan to Genoa and vice versa. The make-up was of 1st/2nd through carriages with sleeping cars of Mitropa (the German equivalent of the Wagon-Lits) being attached in Basel for The Hague. A dining car ran from Genoa to Basel and one from Cologne to Utrecht in this train.

Only people with tickets from Marseille/Genoa to the Netherlands or vice versa could make use of these trains which were not subject to border controls while in transit. The running time was between 21 and 22 hours, some 8 hours better than using the normal services with the border controls and the need to change trains in various places. In Paris, one had to transfer through the city from one station to another to continue the journey, for example.

Coming from the Indies one had to advise the purser aboard before Port Said about the type of travel one wanted: 1st, 2nd, sleeper or couchette and what luggage one intended to take along in the luggage van, because the ship’s passengers used to have many and bulky cases, cabin trunks and luggage compared nowadays with airline passengers. (In those days one used suits for different occasions, no drip-dry or nylon clothing, hats in hat boxes!)

The shipping companies used to carry the big luggage free of charge all the way by ship to the Netherlands, but one had to pay for the luggage carried in the railway luggage van. Generally a day was set on the ship before reaching Port Said for travellers to go into the hold to re-arrange their packing. The purser wired the requirements to Marseille/Genoa, so the railway could form the train consist. There were four different timetables for the Lloyd Rapide, depending on the ship’s arrival in Marseille. From Genoa there was only one timetable.

We got off at Roosendaal where the customs visitation took place and changed trains to go to my grandfather's place in Eindhoven. Grandfather and Tante Marie were waiting for us in Roosendaal. We then went to live at Heerenveen in Friesland. Although war was threatening, it was a terrific time for me travelling on and seeing different trains and trams and soldiery, but this is a different story. Although I didn't know it then, the times would change very much, beyond what we could imagine.